When we look at the early twentieth century photographs of the Swiss Alps, Albert Steiner is always at the forefront. Steiner (1877–1965) captured the Engadine valley and its mountains, in a visual language with which we see the Alps today.

Born in 1877 in Frutigen, in the Bernese Oberland, Steiner was trained in a period when photography was still negotiating its place between science and art. Early apprenticeships in Thun and Geneva grounded him in technical precision, but it was his move to St. Moritz in 1906 that set the course of his career. There, in the Upper Engadine, he found a landscape vast enough to sustain a lifetime of attention.

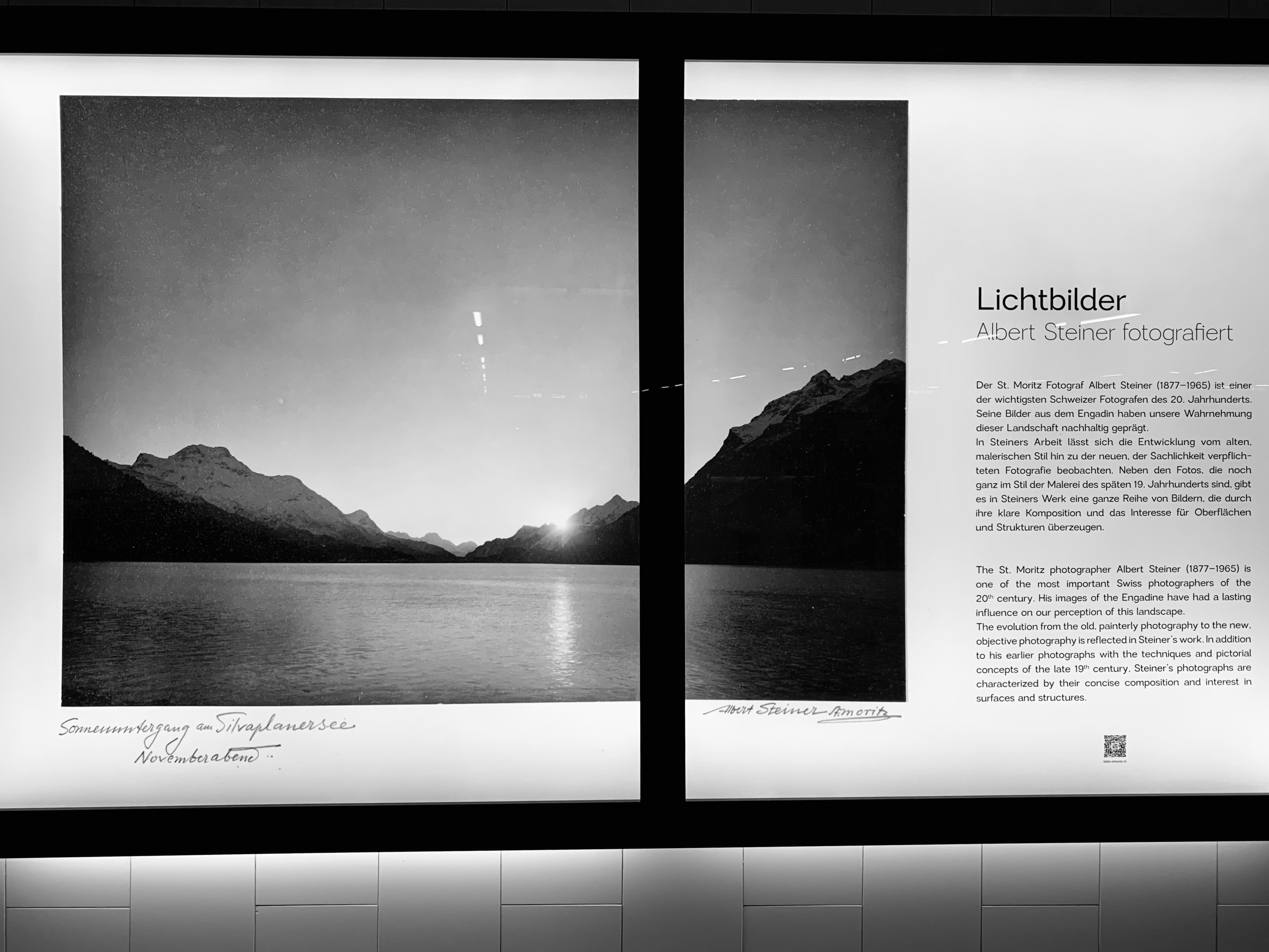

Steiner’s photographs featured a deliberate slowness. He turned repeatedly to glaciers, lakes, and pastures with his most recognisable works defined by restraint. Lakes such as Silvaplana and Sils are rendered as broad planes of tone, where reflections dissolve the boundary between sky and water. The Bernina Range appears as a series of massive, quietly balanced forms. Human figures, when they appear, are small and provisional, absorbed into the scale of the terrain.

What distinguishes Steiner from many of his contemporaries is not dramatic subject matter but his control of atmosphere. The Alps, in Steiner’s hands, become a space for contemplation rather than spectacle.

Stylistically, Steiner stands at a crossroads, inheriting pictorialism the belief that photography can carry poetic meaning, yet he resists its excesses. His prints are not blurred, sentimental, or overtly theatrical. At the same time, he anticipates the clarity of modernism through his disciplined compositions and precise tonal structure. Painters such as Giovanni Segantini and Ferdinand Hodler offered him models for turning landscape into an expression, but Steiner translated these ideas into a distinctly photographic grammar.

Graubünden remained his central laboratory. Beyond the Engadine, he worked in the Bergell, around villages such as Soglio, where autumn scenes balance cultivated terraces against towering rock walls. These images are among his most subtle. Here the Alps are no longer monumental, but intimate, shaped by agriculture, seasons, and long habitation. Steiner’s achievement lies in holding together these two registers, the epic and the domestic, within a single body of work.

His books:

- Engadiner Landschaften (Engadine Landscapes), 1927 - photographic album with views of the Engadine region.

- Schnee, Winter, Sonne (Snow, Winter, Sun), 1930 - 48 black‑and‑white images and text by Felix Moeschlin, focusing on Alpine winter landscapes.

- Die vier Jahreszeiten (The Four Seasons), with Gottardo Segantini, 1938 - a collaborative book exploring seasonal themes through words and images.

- Blumen auf Europas Zinnen, with Karl Foerster, 1949 - a later publication combining Steiner’s nature photography with Foerster’s botanical text.

These helped establish a durable image of Switzerland as a land of clarity, purity, and elevation. These publications were not neutral. They participated in the cultural construction of the Alps as a moral and aesthetic ideal, a place where modern anxieties could be momentarily suspended.

For much of the later twentieth century, Steiner’s reputation faded, eclipsed by newer photographic movements. Recent reassessments, however, reveal how contemporary his concerns remain. In an age preoccupied with speed and saturation, his photographs insist on patience. They ask the viewer to stay with a single ridge, a single reflection, a single shaft of winter light.

In Graubünden today, many of Steiner’s vantage points remain recognisable, even as infrastructure and climate have altered the terrain. What endures is not the accuracy of his record but the attitude it embodies. His Alps are not conquered, consumed, or explained. They are observed with humility, shaped by time, and granted the dignity of silence.

In this sense, Albert Steiner did more than photograph the Alps. He taught us how to look at them.